Art conservation or preservation is often a job associated with museums, as they focus on cleaning, repairing, or documenting historical pieces in an attempt to preserve the artist’s original intent in their work as well as the integrity of the object. Traditionally it has been a very hands-on job, often requiring education from a range of fields such as chemistry, anthropology, studio art, and art history. The digital age however, brings an entirely new level and collective public involvement in the ability to not only document and study, but experience historical works of art in a new and accessible way.

As our society becomes more globalized and modernized, pieces of culture, for example certain languages and art practices are beginning to be lost to time. By bringing together these aspects of history and modern technology, we can not only preserve art beyond its physicality, which is especially relevant in the event it could be lost or damaged, but share it in a way that more people can experience it.

By utilizing 3D scanning and printing technology, museums can now digitally copy, document, and distribute 3-dimensional data of unique and historical artifacts, and some museums, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) are even encouraging visitors to get involved in the process.

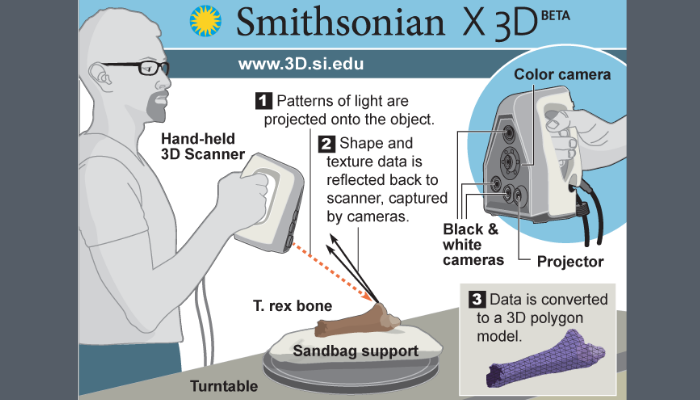

The more professional practice used by museums and businesses, according to Direct Dimensions, a company that works on digitizing 3-Dimensional data, is described a bit like this:

“Using a 3D digitizer, a laser beam is passed over an object. Inside of the digitizer, a camera is mounted that tracks the physical position of the laser beam in 3D space. This 3D data (x,y,z points in space) is transferred to the computer where the object (or subject) is literally “drawn” on the computer as the laser moves over it.”

– Direct Dimensions Website FAQ. Read more about the process here.

These methods such as laser scanning and photogrammetry are used in the initial documentation of the artifact. While museums are more likely to have access to laser scanning— photogrammetry (the process used in 123D Catch), which basically consists of photographs and angle calculation, is accessible by anyone with a working camera.

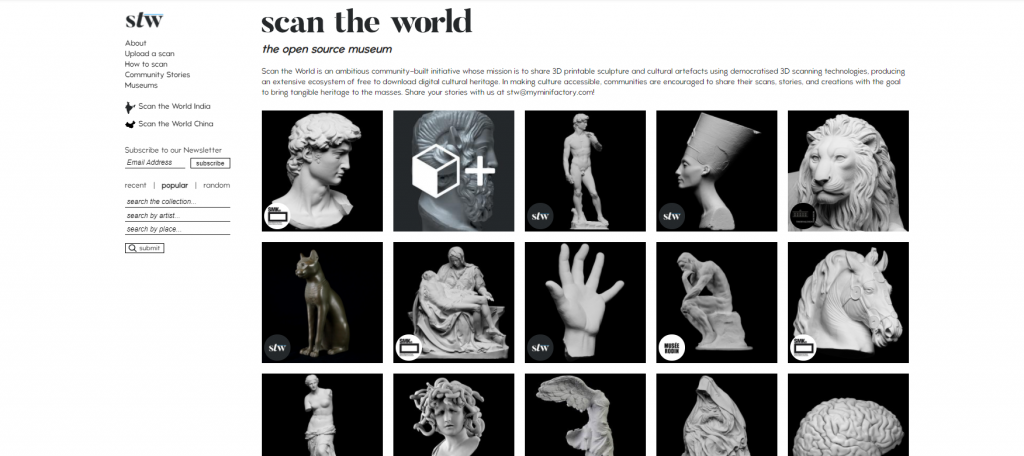

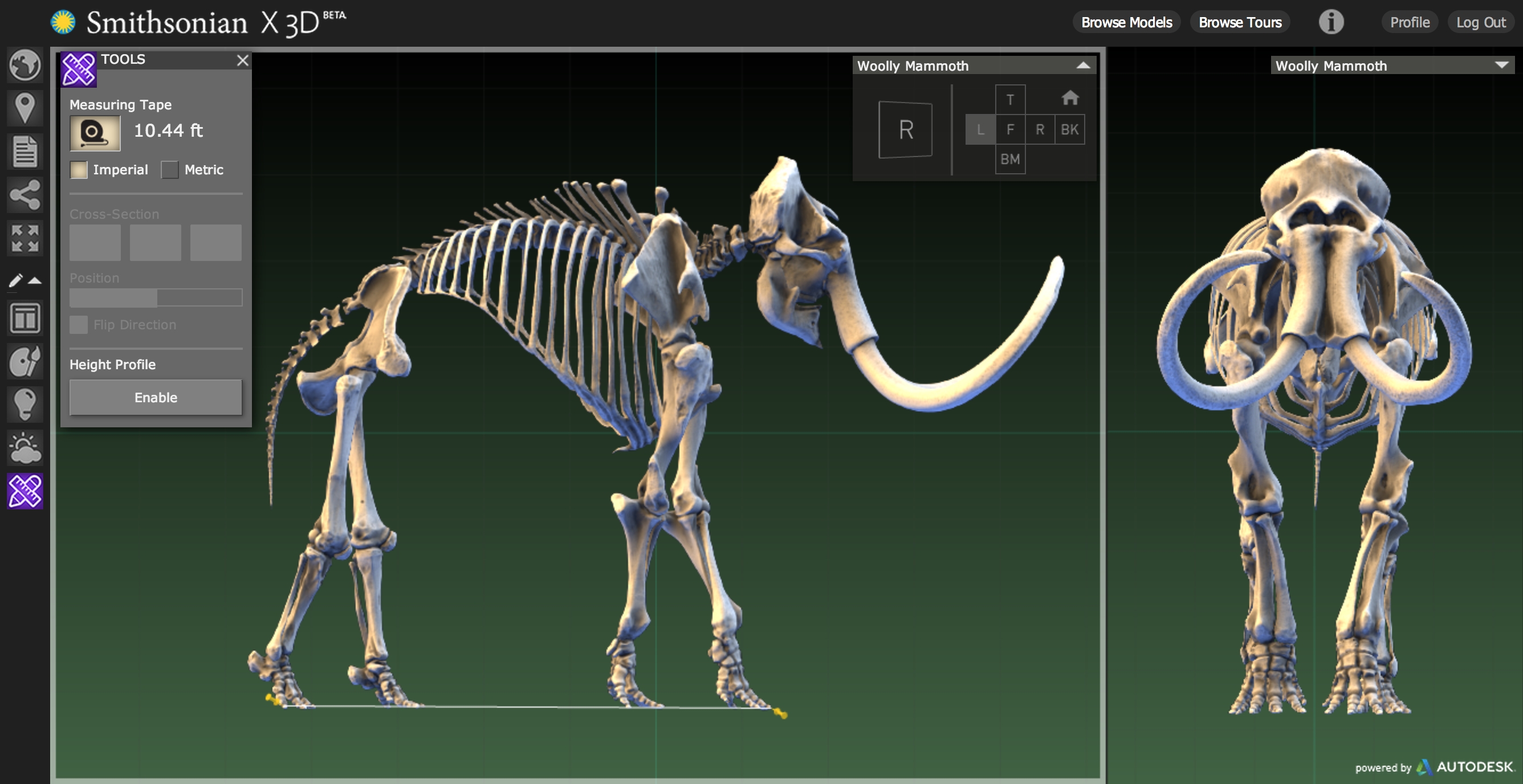

In regards to the online content, not only the MET, but also other well-known museums such as the Smithsonian currently have a substantial amount of 3D models of their collections that are free to access and download online.

These digital archives provide a wide range of new uses and experiences for the public, such as giving people tactile accessibility to objects that would typically be behind a display. This can lead to a variety of new uses, such as exhibits that are made accessible for those who are visually impaired to touch.

Another use that art conservationists use 3D mapping and digitization for is to scan delicate artworks with minimal contact for any degradation and even experiment with digital restoration.

3D modeling also provides artists an opportunity to make transformative art of past works such as this bronze casting of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers by Rob and Nick Carter, who created their mold of the piece using a 3D printed model.

The websites that host the models also serve as a resource that is accessible to people in a wider range of locations, as with all information on the internet. No longer are artifacts tethered to one area or museum collection, and there are no risks associated with the transportation or exposure of delicate pieces. We now have the ability to appreciate, see, and possibly touch historical pieces of art from all over the world thanks to digital fabrication and technology.

While there are many benefits to the availability of these resources, 3D replication brings a need for further discussion on issues specific to the medium, such as copyright laws and the idea of “ownership” in regards to the contents of expensively appraised museum collections. Cosmo Wenman, an artist and design consultant specializing in 3D design, discusses how while some museums are willing to share their scans, many aren’t. Wenman spent three years in a back-and-forth with the Egyptian Museum of Berlin to be able to share an official scan of the Bust of Nefertiti, of which the museum first cited that giving him direct copies of the scan data would “threaten its commercial interests.” The idealized mission of public museums is to preserve and share objects of significant cultural value, so if the original artworks were displayed with the intent for the public to be able to view, why would the scans not be treated in the same way?

As with all mediums, old and new, digital fabrication is yet another tool that has both its own advantages and complications, on top of having uses that are unique in the field of museum conservation. It will be interesting to see if any new ways to use digital tools in museum conservation develop in the future as technology gets even better. With 3D printing technology becoming more affordable and accessible as the medium improves over time, hopefully with the cooperation of museums, more people will be able to participate in and experience art history through digital fabrication.

Additional Sources

https://www.museumnext.com/article/how-museums-are-using-3d-printing/

https://reason.com/2013/06/13/3d-printing-important-for-art-history-no/?itm_source=parsely-api