Cave paintings such as those in the Chauvet Caves and the Sulawesi Caves in Indonesia date back 35,400 years old. The tools prehistoric man used were simple: charcoal, red pigment from animals and their hands. With their hands on the wall, they stencilled the shape of their hands onto the surface of the walls, leaving behind an indexical trace to declare that “[they] were here… This is [their] home”[1]. Driven by this impulse to leave their mark, mankind has continued to find new ways and tools to do so. This impulse to make is intertwined intimately with the desire to create tools to make more and make better. I would propose that Digital Fabrication is the latest development in this desire to create tools to aid in our creations. Thus, this paper argues that Digital Fabrication can be classified as a tool, an extension of the hand of the craftsman, before proceeding to discuss its implication in making in terms of aesthetics, processes, and materials with reference to modern day artists and designers.

Rather than an anomaly, Digital Fabrication should be seen as the latest development in the creation of tools to model what we see. Stephen Hoskins traces the history of 3D printers to that of James Watt’s “machines for copying sculpture” [2]. Hoskins then proceeds to delineate how James Watt’s machines led to new developments which further resulted in more tools that eventually led to the creation of the CNC machine, the predecessor to 3D printing machines. Clearly, creatives have been creating new tools to better meet their needs to model and replicate what they observe. This desire to create better tools to model reality eventually birthed Digital Fabrication processes in the age of Digital technology. Thus, Digital Fabrication came from a collision between modern Digital technologies and the historic urge to create tools to replicate reality. In this context, Digital Fabrication should not be seen as an anomaly but as a new tool for creatives to employ to meet their needs in replicating reality.

Having firmly taken its place as a new tool available for creatives to model reality, it is imperative to discuss Digital Fabrication’s impact on aesthetics, processes and materials, all of which are important elements to art-making.

Aesthetics, the theory of beauty, has often been linked to the notion of craftsmanship. Digital Fabrication, which “makes the object twice removed from its creator” [3] widens the distance between maker and material. At first glance, it may appear to undermine craftsmanship as what took hours of hard labor is now made by robotic arms. Though seemingly problematic on the surface, this phenomenon is not new. Since the first use of hands to make, man has created many more tools such as the brush or the hammer to aid in making. These tools, like Digital Fabrication, serve as an extension of the maker’s hands and gradually widened the distance between the maker and object. The transition from an analogue appendage to a digital appendage is a non-issue. In fact, this ‘problem’ detracts from the actual problem, the separation between “hand and head” [4] according to Richard Sennet in his seminal work The Craftsman. Tellingly, Sennet warns of how the “circular metamorphosis” of practice can be aborted by CAD. The issue Sennet takes is one against laziness and complacency rather than the distance between maker and object. His warning of “misuse” of digital processes suggests that the pitfall of Digital Fabrication lies on the maker’s approach. If the maker views Digital Fabrication primarily as a shortcut or a crutch, adopting an attitude of complacency or laziness, he would be unable to learn from his digital ‘hand’ and fails to improve his craft. Conversely, if he learns from the feedback from his digital ‘hand’ and practices consistently to develop skilfulness, he will have developed craftsmanship grounded on “skill developed to a high degree” [5]. Thus, Digital Fabrication can and should be seen as a digital ‘third arm’ that should be trained and developed for the maker to craft objects worthy of being deemed beautiful.

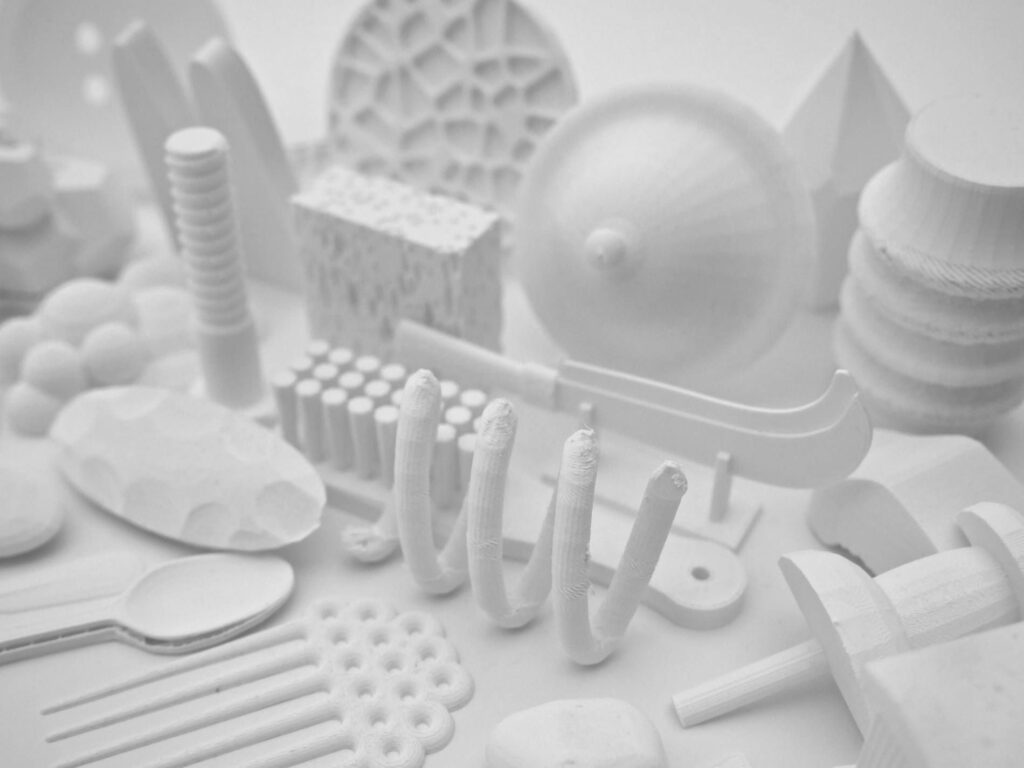

In view of this, the 3D printed works of Michael Eden and Lee Taekyeom, both of which are skilfully made after repeated tests and experiments with Digital Fabrication processes, are objects of high craftsmanship. Strong craftsmanship thus warrant them attention and admiration.

Apart from Aesthetics, Digital Fabrication also has implications for art-making processes. The transition from an analogue interface to that of a digital interface means greater potential for data input and processing. With analogue methods, creatives faced constraints in space and computing. Sketchbooks could only contain so many drawings and the creative can only process so many images in his mind. With digital methods, memory and processing powers are magnified. This is exemplified in Debbie Ding’s and Liu Xiao Dong’s works which employ Digital Fabrication processes to harness data points to create works that would have been near impossible to create with analogue methods. Thus, the new digital arm can assist the artist in capturing more data and processing them at a much faster and consistent manner. This opens new avenues or types of art such as Data art.

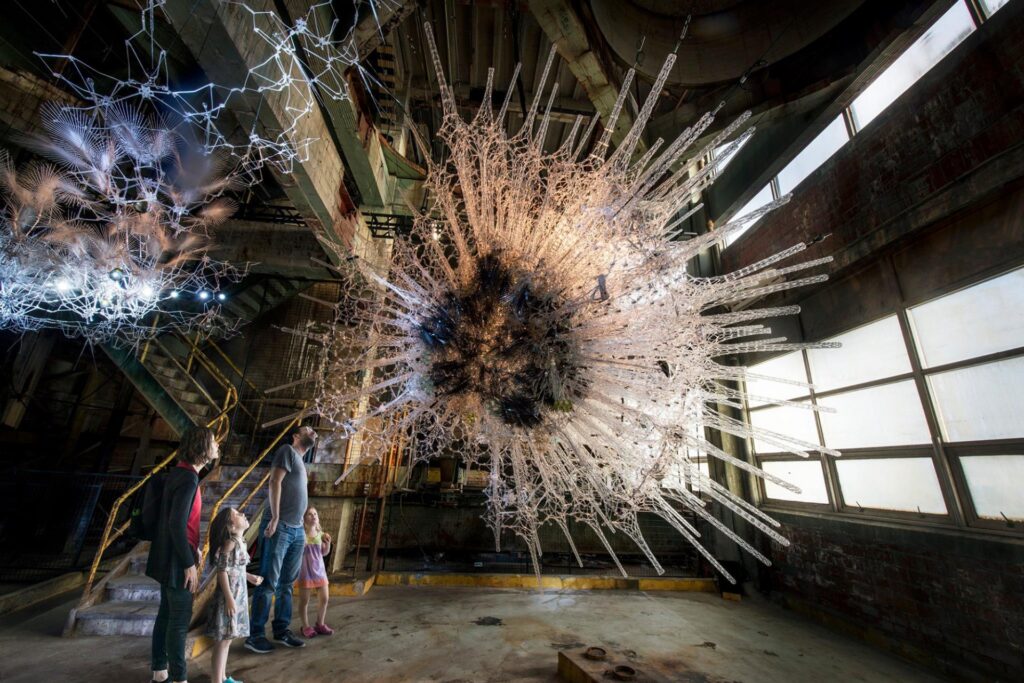

Lastly, Digital Fabrication also opens new frontiers in the domain of materials, allowing creatives to manipulate traditional materials in old ways and even explore new materials. The accuracy of Digital Fabrication tools allows for intricate work such as Marianne Forrest’s tiny timepieces. Its consistency allows sculptors like Rick Becker to create small scale models of their works. “Freeform modelling” [6], a new way of modelling made available by 3D printed works, allows previously inconceivable works to be created such as those of Philip Beesley.

To sum up, digital fabrication can and should be seen as the latest iteration amongst the many tools man have created to aid in their creative pursuits. As with analogue tools, digital fabrication opens up unique ways of conceptualizing, making, and modelling forms. Thus what remains critical is for creatives to master these tools. The aim should be to adeptly control the tools, analogue or digital, and not let the tools control them.

Citations:

[1] Marchant, Jo. “A Journey to the Oldest Cave Paintings in the World.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, January 1, 2016. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/journey-oldest-cave-paintings-world-180957685/.

[2] Hoskins, Stephen. 3D Printing for Artists, Designers and Makers. 2nd ed. London, England: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

[3] Ibid

[4] Sennett, Richard. The Craftsman. London: Penguin, 2009.

[5] Ibid

[6] “3D Printed Art: 5 Ways 3D Printing Pushes the Boundaries of Creativity.” Formlabs, July 22, 2019. https://formlabs.com/blog/3d-printed-art/.