Inscribed on UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, the tradition of papercutting is an important practice originating from China which holds the cultural fabric of many centuries. Under the influence of modern digital technology, how do these tools contribute to or detract from the preservation of this art form?

Going as far back as the 6th century, papercutting has been a popular folk craft in China used for celebration, ritual, and decoration. Most popularly seen during the Spring Festival, Lunar New Year, and weddings, papercuttings often express wishes and hopes. Following superstitious beliefs, they have also been burned to accompany the dead at funerals. While there are different ‘schools’ based on various regions, papercuts are typically scissor-cut from red paper and commonly feature animals (like those of the zodiac), people, Chinese characters, patterns, and more. Adorning walls, windows, doors, and other parts of the home, this folk craft was primarily passed down through the women and girls in rural families.

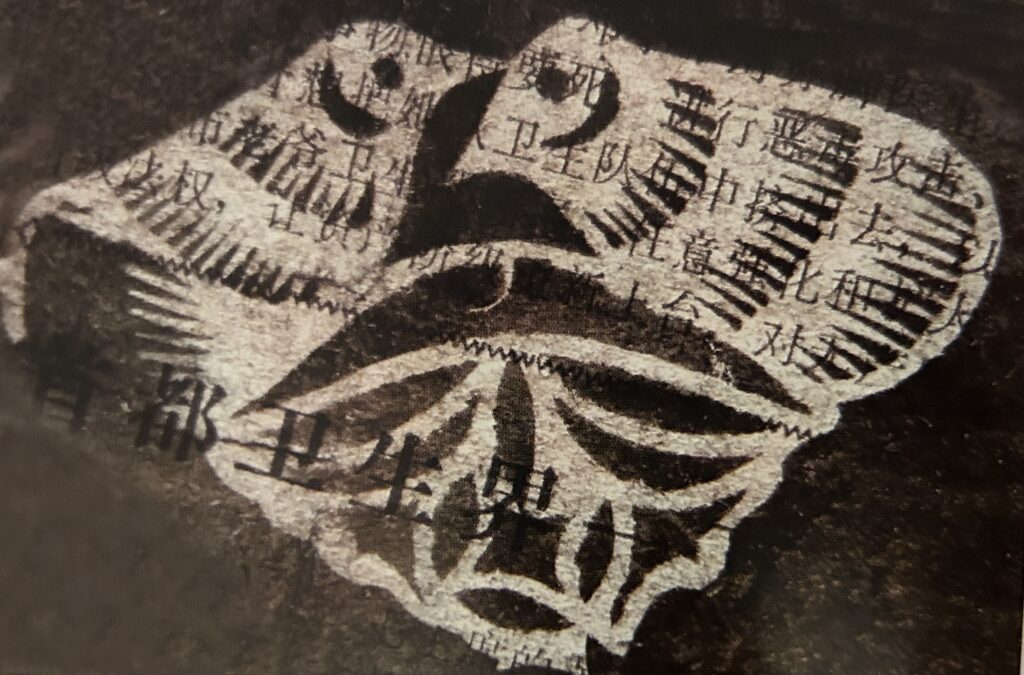

During the Cultural Revolution from 1966-1976 in an anti-intellectual cleansing, the Chinese Communist Party under Chairman Mao Zedong condemned traditional art forms of the intelligentsia such as ink paintings. Instead, the CCP promoted folk art practices such as papercutting done on farms or in rural villages in the official systems of art as they better represented the working class. As such, paper cuts also became a popular medium for propaganda.

In her article, “Making the Cut: The effects of the introduction of Computer Numerical Control (CNC) on the Chinese papercutting 2006-2018,” writer Pamela See observes how the digitization of this process was catalyzed in the mid-2000s when photocopiers allowed anyone with access to the technology to replicate the designs with a photocopy and blade. See states that as these designs traditionally were passed intergenerationally within families, the intervention of this technology “enabled democratic entry into an exclusive cohort.” As this led to an indiscriminate appropriation of papercut designs, it became difficult to classify their ethnographic origins and value. By the 2010s, the Chinese domestic market would be dominated by printed stickers of papercut designs on clear film or traditional motifs laser cut into a “paper” of felt-like consistency. “The diversity of Chinese papercutting may have been completely eradicated by the ‘universalism’ imposed by corporations that control the ‘means of production’ during the post-digital era,” cautions See.

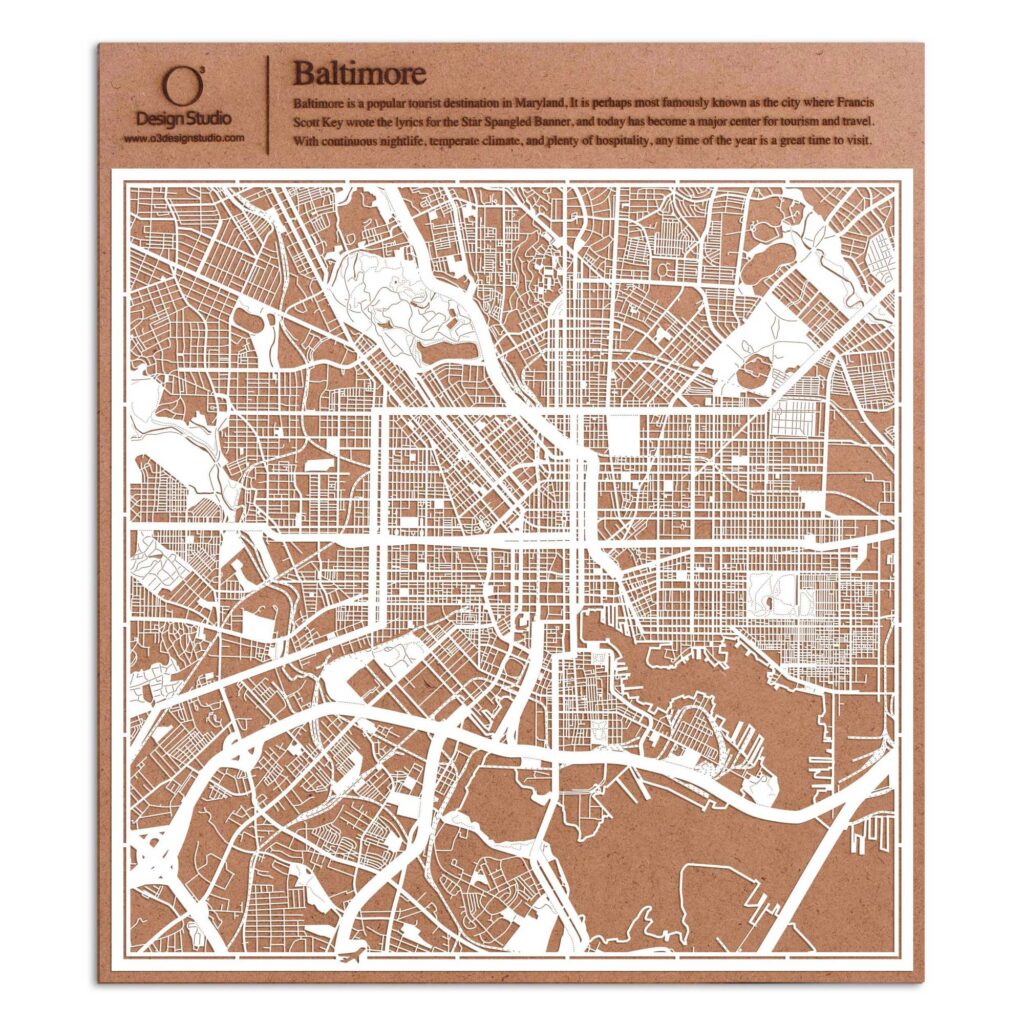

A staunch example of how CNC processes have ‘modernized’ papercuts is O3 Design Studios’ laser-cut city map gifts. Set up by two Beijing-based designers, the studio appeals to a global audience with designs of cities from almost every continent. In their About Us page they clarify, “We do not highlight that our products are hand-made, because such accuracy degree cannot be reached by hand. They give priority to the machining, supplemented by hand, and then reach the extreme accuracy.” Criticizing their ‘exploitation’ of CNC technology to create products unachievable by hand, See recognizes O3 Design Studios as unapologetic technological determinists. Indeed, they lean into the fetish of technological advancement and extreme accuracy. These pieces are marketed for the spectacle of their detail and a sterilization from Chinese tradition, clutching audiences from around the world which do not need to apprehend Chinese regional heritage.

However, as we enter conversations of what it means to maintain tradition, we must first define it. In Carol Yinghua Lu’s essay, “After Tradition: The Notion of Tradition as a Projection of Subjectivity in Contemporary Art Practice in China,” the art critic aims to break down the dichotomic fallacy of equating Chinese tradition as fixed, absolute, and legitimate understandings that separate its current state from the West. She employs Edward Shils’ definition of ‘tradition’ as anything transmitted or handed down from the past to the present, such as objects, language, awareness, and thoughts. Open for reiteration, tradition in Lu’s eyes is not a fixed set of aesthetic principles, but a dynamic and mutable ideological structure that can coexist successfully with modernity.

In a series of interviews of acclaimed contemporary papercut artist Liu Jinglan, Liu contends with the issue of maintaining tradition while appealing to a new market in her own non-digitized process. The commitment to scissors is more than humble. There’s a commitment to ritual to the simplicity of these tools as she grinds the blades on a whetstone. When praised for her skilled cuts, she remarks, “our ancestors have helped me; it’s our ancestors’ heritage that is great.”

Interestingly, Liu believes that what makes modern paper cuts crude is how they are less concise and vivid. She holds that “In the past the artist was bolder; to give only a suggestion for the bird was enough. Simple as that is, it is impressive.” These traditional values that craftswoman Liu appreciates is the antithesis of the work by the highly detailed maps created by O3 Design Studios. Comparing these artists, Liu captures a spirit of communal devotion and magic in humility which are far lost in the transmutations by O3. Sharing her observations that what is seldom seen in life is frequently seen in old papercuttings, her own work carries the traditions of imagination and beauty.

Currently, the changes to the market have meant that instead of just being a daily commodity, papercuts made by craftspeople are a cultural icon with a higher price tag. As newer generations are not as interested in folk art, maintaining the transmission of this art form has not been easy. Like the ways Liu has adapted old papercuts in her contemporary renditions, innovation does not have to abandon tradition. While tools like the laser cutter aids with maintaining popularity and access through mass production, it also has appropriated and disengaged the populace from regional legacies. Perhaps then, we can understand some laser cut designs as a part of a culture of the digital which is geographically amorphous. As artists continue to use new tools to innovate their cultural work, a middle ground can be found in understanding that tradition as a gift and with each new set of hands holds magic and responsibility.

Sources

Carol Yinghua Lu, After Tradition: The Notion of Tradition as a Projection of Subjectivity in Contemporary Art Practice in China, Unscrolled: Reframing Tradition in Contemporary Chinese Art (London/Vancouver: Black Dog Publishing, 2015).

https://garlandmag.com/article/chinese-papercutting

Sun Bingshan, Chinese Paper-Cuts (Beijing: China Intercontinental Press, 2007).

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/art/2013-08/07/content_16876760_2.htm

https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/culture/paper-cut.htm https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202301/31/WS63d85d6aa31057c47ebabf03_6.html