Throughout recent decades, there has been a fascinating sort of intersection between digital fabrication techniques and fine art that has brought up the ethics of digitizing the art making process. With the emergence of technologies such as 3D printing, 3D scanning, and CNC machining, also known as computer numerical control, digital fabrication has been opening entire new realms of creativity for artists to explore, even so far as to making nearly impossible or labor intensive projects much easier to access and control, as well as extending into the realm of art preservation and cataloging.

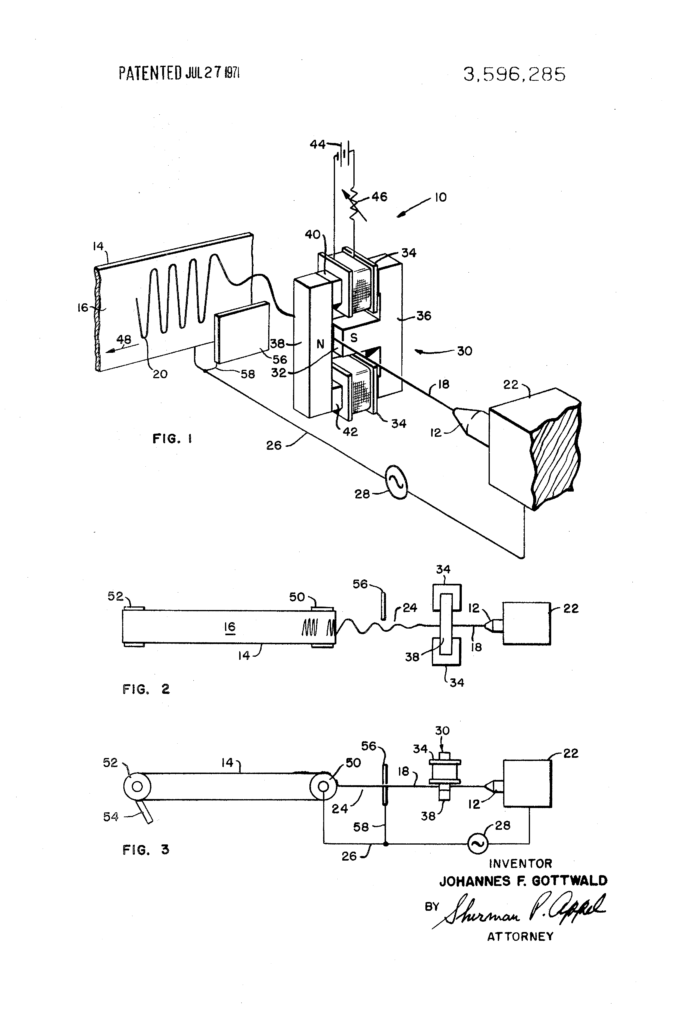

3D printing has been an incredible technology that actually has a patent dating to 1971, when Johannes F. Gottwald made a machine called the Liquid Metal Recorder, capable of creating an object using molten metal that would solidify into a shape with each pass and subsequent layer of material that the machine would output. This patent was the precursor to the material extrusion process, and in 1980 Dr. Hideo Kodama suggested methods using thermoset polymer instead of metal as a material. While this didn’t result in much further interest in the idea, the foundation for advancements in the technology was laid, and over the subsequent years numerous and more capable models would emerge onto the market, focusing on the extrusion of a material through a nozzle to build forms over the course of hundreds or thousands of layers. In the present day, common material examples used in 3D printers would be polylactic acid, and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, and metals, but have even been extending into materials such as ceramic polymers and graphene.

Photo sourced from Google Patents

Given this breadth of material options and fine tuning of shape and form, it is no wonder that many artists have been curious at trying their hand at these techniques. A wonderful example of one such creative person would be Lionel T. Dean, who is a designer focusing on sculptural home furnishings created with 3d printing techniques. Using mediums such as glass fiber, resin, and various metals, his works evoke a somewhat organic and alien aesthetic, letting a simple object like a stool stand alone as a sculptural piece. His works have been displayed at galleries even as prestigious as MoMa.

“The Alchemist”, 2023

Material and Technique: 3D Printing, Glass Fibre, Polished Resin Finish

Dimensions: 65cm H x 53cm W x 53cm D

Image sourced from FutureFactory Studios

3D scanning is also used in many areas of art. One could 3D scan an object to then be manipulated in a software for further 3d printing or visualizing, or scan and print it to the exact detail, the latter of which can more importantly can be used for the extremely crucial purpose of preserving multitudes of art works. For example, the Smithsonian has scanned thousands of artifacts and 3d artworks for historical preservation. Doing this gives the institute the ability to record objects with one hundred percent clarity in size and detail! Many museums have embarked on the attempt to digitize their sculptural and three dimensional collections for cataloging, and have even gone so far as to release the scans for public use, so anyone with access to a printer can fabricate a detailed model to whatever scaling they so choose for whatever purposes they may have. Scan the World is an effort which aims to 3D scan as many artworks as possible for a greater understanding of cultural heritage. This sort of preservation allows for nearly universal access to art pieces that until then may have required extensive travel to study, thus raising the world’s artistic vernacular in exponential degrees.

Image sourced from the Smithsonian Museum

When it comes to CNC, or computer numerical control, there are ways in which one could see it similar to 3D printing in the sense of creating a three dimensional form using a predetermined material. But while 3D printing is additive, CNC machining is subtractive, capable of using routers, drills, and mills to create incredibly complex and intricately designed forms and shapes out of a healthy choice of materials, giving artists unprecedented control to size, dimension, and detail. For example, the American sculptor Barry X Ball uses CNC techniques in this way of reclaiming classical sculpture. He begins by 3D scanning specific classical sculptures, and then goes about finding a new appropriate material to then remake the sculpture in said medium, allowing for the exact recreation of the work while at the same time giving it an entirely new appearance.

In the background sits “La Purita” by Antonio Corradini (1668-1752), another sculpture that Ball would tackle.

Images sourced from Barry X Ball’s website

This is just one way to go about making dimensional work using CNC however. CNC can also be ordered to mill entirely made up, fashioned forms, with the added ability of being able to figure out many logistical and mathematical issues through the process of making the file that the machine ultimately uses to output its commands. A good example of this would be the Dragon Skin Pavilion by architects Emmi Keskisarja, Kristof Crolla, Sebastien Delegrange, and Pekka Tynkkynen, an architectural sculpture that was first displayed at an architectural biennale in Hong Kong. “The sole material used in the pavilion is post-formable Grada Plywood, a brand new material that seems to revolutionize the bent plywood industry. A CNC-router was used to make a wooden mould in which pre-heated flat rectangular pieces were bent into shape. A computer programmed 3D master model generated the cutting files for those pieces in a file-to-factory process: algorithmic procedures were scripted to give every rectangular component their precisely calculated slots for the sliding joints, all in gradually shifting positions and angles to give the final assembled pavilion its curved form.” This process perfectly highlights the ease at which CNC can be used for near inhuman artistic endeavors, with the ability to streamline the making process to an extreme degree compared to what it used to entail.

Emmi Keskisarja, Kristof Crolla, Sebastien Delegrange, and Pekka Tynkkynen

Image sourced from Arch Daily

While these digital techniques have been discussed in a more positive light until now, it is worth it to mention the ways in which artists have felt slightly hostile towards these emerging mediums. The fine art industry always has trouble trying to come to terms with new techniques that make something “easier” or “more obvious” to make, which makes sense given that artists put a lot of emphasis on the process itself, as every movement and choice you make up to that point will greatly affect the final outcome. In the case of digital fabrication, one could easily see how processes such as 3D printing, 3D scanning, and CNC can threaten artists and their work, as in a way it is greatly expanding the access to art making, as well as bringing up the question of if something digitally fabricated requires the same effort, thought, training, and natural skill as something made manually to the point of them both having as much of a place in art institutions, museums, and auctions. Personally I am enjoying the emergence of these techniques and all the wonderful doors they are opening, and definitely think they can coexist along more established fine art practices and approaches.