How interfaces expand and contract possibilities

Via lines of code, numerical points in space and all the edges inbetween, the world around us is now conceived through screens. A vast majority of things are designed digitally–our clothes, devices and appliances, and even our homes; their surrounding buildings and the streets connecting them. Despite this rapid spread of digital fabrication, the ways in which we design have largely stayed the same since its beginnings. That is, the core principles behind the interfaces have not changed. Productivity and precision define their values—ideals originally driven by economic and defense efforts of the 20th century. But as computers become more and more accessible, and production of media and digital based culture expands, it’s becoming increasingly evident that the dominant approach for designing these interfaces has lagged behind, precisely due to the obsession with precision and need for repitition. Their issue is not one of efficiency in production (they’re undeniably great at this), but in their inability to fully integrate with wider histories of cultural expression.

What opportunities might we find if we decouple the idea that these programs have to be tools? What if they became toys to be played with, or experiences for social gatherings? What possibilities become apparent when we reconsider the long assumed relationships between people, machines, and materials in this process? With a rejuvenated approach we might discover design fictions to be no fictions at all. The argument here will not be to gawk at current approaches, as these are still very much worthwhile exploring. Instead, we will cross into the unknown, and explore some of the creative potentials that digital fabrication has yet to tap into.

A History on Interfaces

Looking back on the history of computer interfaces, a clear thread of progress reveals itself: a story that is as much about possession and defense, as at it is about wonder and creativity. The idea of computing began in the early 19th century, when Charles Babbage, a mathematician and philosopher from London, imagined a machine that could calculate formulas automatically. This idea would later be called the Analytical Engine, which was derived from the Difference Engine, an earlier project of his. This device promised to calculate much faster than a human, a necessity of the time when humans were the best computers we had. With this passion and necessity, Babbage then mentored Ada Lovelace, who, enamored by mathematics, wrote algorithms that would be executed by the machine. Her writing was practically the first written computer program. Sadly, the Analytical Engine was never fully realized, but the dream of computing had just been born out of both a fascination for mathematics and the need of profit and production. The concept behind this engine and the structure of Lovelace’s function are still represantive of modern computers. 200 years later, their work is still used today to teach the principles of computing.

In the midst of WW!! the first digital and programmable computers were developped. ENIAC was the first of its kind, designed in 1946 with the sole purpose of decrypting German messages and predicting the paths of ballistic artillery. It’s safe to say that, in face of an impending missile shot in your direction, calculating its path precisely was of upmost importance. And thus, precision began to ground itself as a core value for computers, and subsequently, their interfaces.

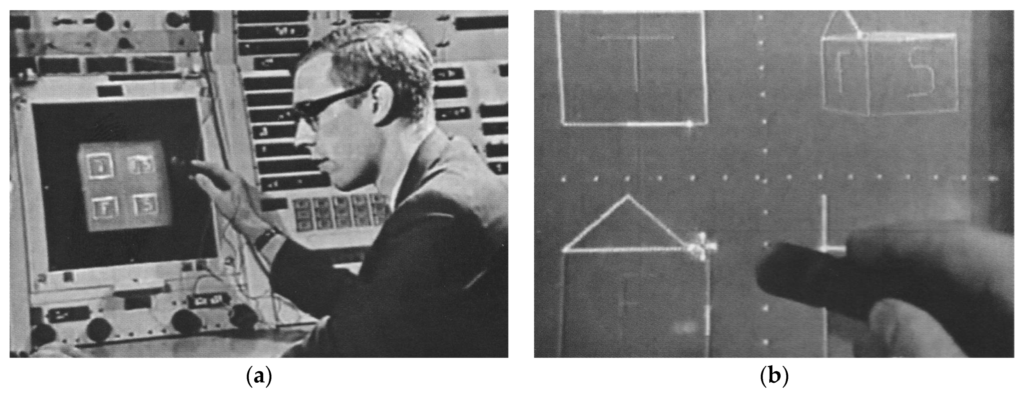

Stepping closer to the ways in which we make with machines, Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad (a.k.a. Robot Draftsman) was a major breakthrough in human—computer interaction, and started the paradigm of graphical user interfaces. Sketchpad was the very first interactive system built for computers, which allowed for people draw and manipulate lines with a light pen.

Redefining the Interface

Picture yourself before a large block of marble, towering well above your eyesight. With bare hands alone, its hard edges and solid body are practically immutable; you’d even be hard at work trying to move it anywhere. But look down and grab the chisel laying on the floor, and magically watch as these barriers fall. In this immediate moment of recognition, the chisel has irrevocably opened the marble to us and transformed it into a site full of possibility. No longer just a wall, the stone is now a journey and a destination. Our relative positions have drifted, and the extents of our bodies are now capable of joining in dance together in a way otherwise not possible before.

Amidst all this opening, the chisel has also set impassable restrictions on the posibilities of interaction. As long as I keep the chisel at hand, I won’t be able to glide my palm over and feel its cold surface, or paint on it with a brush. But it is only with this chisel that I can carve my ideas into the stone. If I decided to drop the chisel and in its place grab emery paper, I could swiftly polish the surface. But the task of sculpting into the marble now seems close to impossible again. Alternatively, trying to reach that smooth and polished finish with the chisel alone would be futile.

In all of these cases, the objects we choose to use act as the interface between us and the marble. They are a point of convergence between bodies. And for these interfaces to create contact at all, they need to exclude everything where they don’t. It is in this way that our relative positions are calculated, defining the surface of possible interaction.

“a surface forming a common boundary of two bodies, spaces, or phases”

The definition above is mainly used in the language of physics, more likely to refer to an oil-water interface than our chisel above. But the word choice of a surface will become necessary as we bring it into a wider perspective of interfaces. Surfaces are the outermost layer of things (when closed), the point of contact between exteriors and interiors, and interfaces are no different. An interface is a bounded surface between bodies, bounded not in any literal sense, but by a set perimeter of interaction. It delineates a set of possibilities and impossibilites within the given system.

In this act of exclusion, neutrality becomes a lost cause. Interfaces will always favor a certain approach and a specific system of values. This isn’t to be frowned upon, as it is in this same way that possibility is even carved out in the first place. But it does make something very apparent: when designing an interface, we must equally consider the doors we close as much as the ones we open. In the context of digital fabrication, it means to critically asses our value systems in order to make way for the unnoticed and underrespresented forms of making within the field.

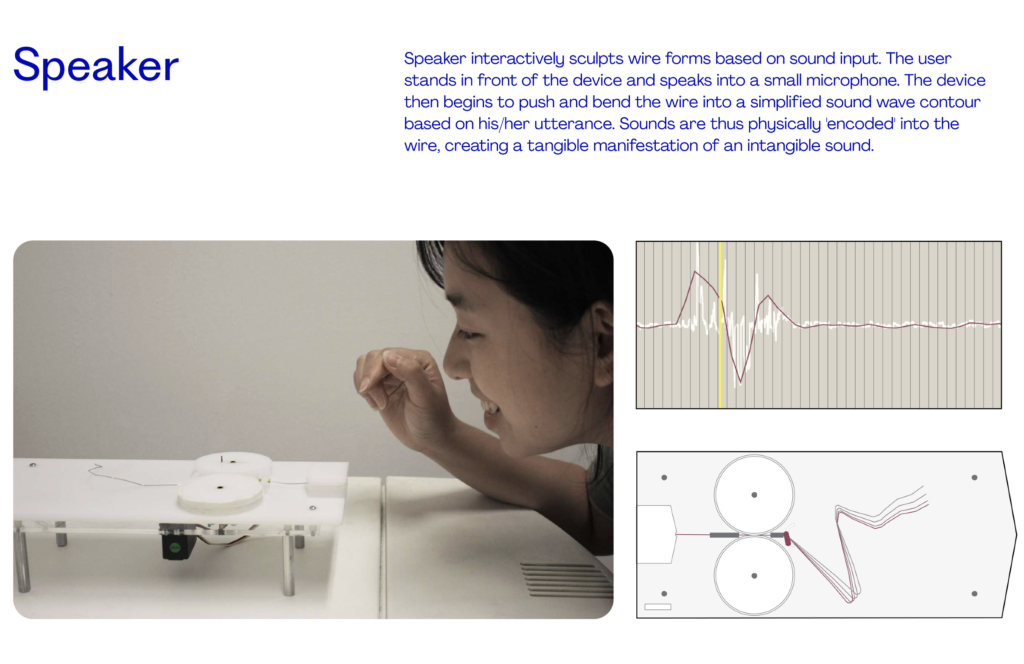

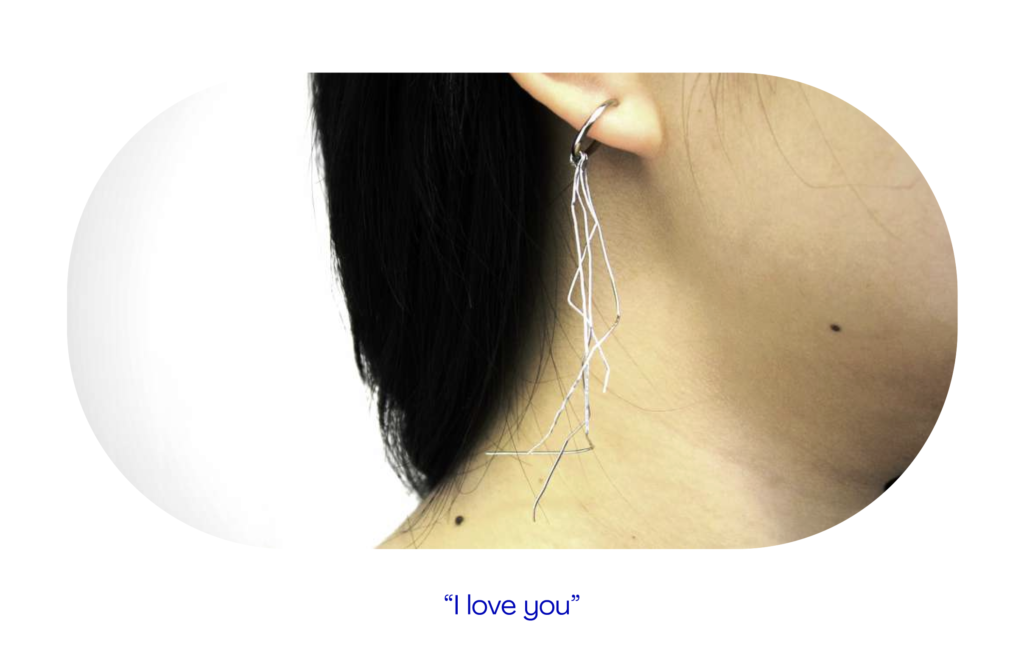

Alternative Interfaces

Having traced the history that led to the dominant interfaces for fabrication, as well as the inherent exclusion within any system, the potential of alternative interfaces for creative exploration becomes much more apparent. Following this text are a few of these alternative examples, specifically from a group of designers looking to bridge the gap between materials and interfaces. When looking at these, I’d invite you to question: how do interfaces influence the work done? And, how can we utilize any interface in ways that they may have not been designed for? It is in this probing of their horizons that we might find unique opportunities for creative expression.